In the age of false news: A journalist, a murder, and the pursuit of an unfinished investigation in India

In 2017, journalist Gauri Lankesh was assassinated in Bangalore days before she planned to publish an article about disinformation. Over five years later, Forbidden Stories pursued Lankesh’s work on fake news and explored new leads in her murder case.

By Phineas Rueckert

Additional reporting by Srishti Jaswal for Forbidden Stories.

Oishika Neogi (Confluence Media), Prajwal Bhat (The News Minute) and Laura Höflinger (Der Spiegel) contributed interviews and research.

Infographics: Guillaume Meigniez

STORY KILLERS | February 14, 2023

On September 5, 2017, 55-year-old journalist Gauri Lankesh arrived late at her office in Bangalore. It was a warm day with a light wind in this southern Indian city known for its breezy weather and traffic. At her office, the ground floor of a faded yellow, three-story building on a residential street, she reviewed the upcoming issue of her weekly magazine and put the finishing touches on her editorial, which she always wrote last.

Concerns about the rise of disinformation in India and her experience as a high-profile target of digital hate campaigns weighed on Lankesh as she wrote the piece, which she titled, “In the Age of False News.” Lankesh elucidated how “lie-factories” – websites that traffic in rumors and half-truths – spread disinformation in India. She detailed a viral rumor about censorship of a Hindu idol by the opposition party, tracing it to one of the most virulent of these sites called Postcard News, run by a local entrepreneur named Mahesh Vikram Hegde. The rumor, she elaborated, was further spread by the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and other politically-motivated individuals who “used the fake news as their weapon,” she wrote.

She had been finessing the article for several days, and it was meant to come out two days later. Setting the piece aside, she was in an uncharacteristically cheerful mood, friends and family remember, and spent the afternoon chatting with feminist activists.

Dusk had settled over Bangalore as Lankesh headed home, weaving through the streets of India’s bustling tech capital. Had it been another night, she might have dropped by her sister’s house to binge-watch the show “This Is Us,” as she had done on prior evenings. Instead, she went straight to her home, in a hamlet of calm where loud noises are uncharacteristic. As Lankesh walked up to the entryway of her house, the cracks of four gunshots echoed through the neighborhood. The first shot hit Lankesh below her right shoulder on her back. Two bullets lodged in her abdomen, piercing her vital organs, while a fourth ricocheted off the wall of her house. A motorcyclist and his accomplice fled the scene, shielding their faces from CCTV cameras.

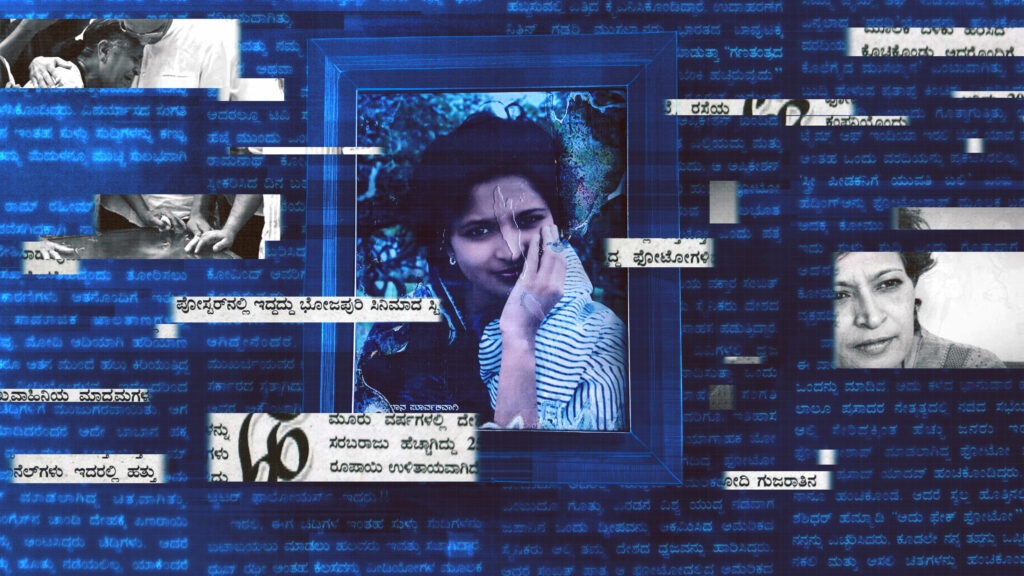

Journalist Gauri Lankesh circa 2015. Photo courtesy of Sheetal Jain.

Lankesh – who died instantly – never saw her editorial in print.

Lankesh’s murder soon sent shockwaves across India. Hundreds of mourners attended her funeral, holding signs reading, “I am also Gauri.” Within a couple of years, police investigators arrested 17 suspects, all associated with the Hindu nationalist cult Sanatan Sanstha, its affiliate Hindu Janajagruti Samiti (HJS) and other fringe religious groups. (An 18th suspect is still at-large.) Members of this unnamed syndicate plotted the assassination for over a year, obtaining weapons, training hired guns and tracking Lankesh’s daily movements, according to police sources. (A trial is currently ongoing in Bangalore. In an email, a Sanatan Sanstha representative wrote: “Your questions pertain to a case that is subjudice. It would be inappropriate to comment on such matters as the Indian judiciary is an independent body.”)

Forbidden Stories, whose mission is to continue the work of threatened, imprisoned or assassinated journalists, pursued Lankesh’s unfinished work. Starting from Lankesh’s premise – that disinformation has become both industrial and weaponized – Forbidden Stories gathered a consortium of 100 journalists from 30 media outlets to investigate the global disinformation-for-hire market as part of the “Story Killers” project. From India to South America to the heart of Europe, journalists peeled back the layers of a growing and unregulated market, ranging from small-time fake news peddlers to multinational mercenaries selling disinformation campaigns aimed at subverting democracies.

Now just over five years after Lankesh’s murder, Forbidden Stories accessed case files, spoke with local police and lawyers, and investigated an unexplored lead in the criminal investigation: how a viral 2012 YouTube video of Lankesh spread across social media and was later shown to the people who allegedly killed her as “justification” for her murder.

Protesters hold a sign calling for justice in the murders of Lankesh and other intellectuals at the #NotInMyName protest in Bangalore. Photo: Joe Athialy/Wikimedia

An inconvenient journalist

Lankesh is now a towering figure in Bangalore, where she grew up and later returned in her late 30s. At Koshy’s, an old-fashioned dining hall where Lankesh was a regular, restaurant owner Prem Koshy still thinks of the seat near the window as hers. Reporters look back fondly on interactions with Lankesh, who some say inspired them to join the field.

But before her death, Lankesh was not a household name, unlike her father. Author of the eponymous Lankesh Patrike – or “Lankesh’s Paper” in Kannada, the local language – P Lankesh was famous for his investigations on corruption and politics during a time many consider the golden era of Indian journalism – a period of unprecedented editorial independence starting in the early 1980s.

“My father had brought down governments with his exposes on corruption,” Kavitha Lankesh, Lankesh’s younger sister, told Forbidden Stories in her Bangalore office, located upstairs from where Lankesh had once worked.

Lankesh, she explained, had not started journalism with such ambitions.

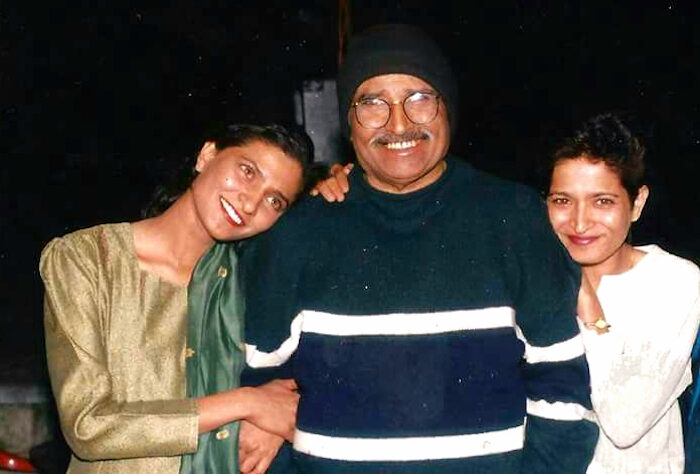

Gauri Lankesh (right) poses for a picture alongside her sister Kavitha and father, P Lankesh. Photo courtesy of Kavitha Lankesh.

Lankesh began her career in Delhi, writing everything from criminal investigations to profiles for Times of India, ETV Telugu and Sunday Magazine. It wasn’t until 2000, when she returned to Bangalore to take over Lankesh Patrike after her father died, that Lankesh’s writing took a political turn and her tongue a sharper edge. The move, colleagues and family recall, led to a “transformation” in how Lankesh understood her role as a journalist.

In 2005, Lankesh created a weekly, naming it Gauri Lankesh Patrike. In editorials and reportage from remote regions of Karnataka, her home state, the Patrike took on the establishment and railed against the rise of far-right Hindu nationalists. The paper investigated illegal mining in north Karnataka, local corruption and religious polarization. One of its main targets, however, was the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party – or BJP. (Twice, Lankesh was accused of defamation by Pralhad Joshi, a BJP member of parliament.)

Lankesh, who described herself as a journalist-activist, saw combating fake news spread by the BJP as part of a larger battle against the Indian far-right, colleagues said. “The magazine that she was editing for more than a decade was working against [communal disharmony],” Dr HV Vasu, a colleague, told Forbidden Stories, referring to inter-religious conflict in India. “So fighting fake news was very much integral to that.”

Journalist Gauri Lankesh during a year abroad in Paris. Photo courtesy of Kavitha Lankesh.

Even in her early years running the Patrike, Lankesh’s writing underscored the harm of politicians manipulating information. “He believes in the power of a lie acquiring the garb of truth with constant repetition,” she wrote of former BJP Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee. In another article debunking a viral rumor, she referred to “the fake ‘facts’ of history,” alluding to claims that a former ruler from the region had attempted to forcibly convert Hindus to Islam.

Her greater visibility as a journalist and activist contesting Hindu nationalism may have troubled powerful interests in Karnataka, considered by some to be a laboratory for seeding narratives that create religious strife.

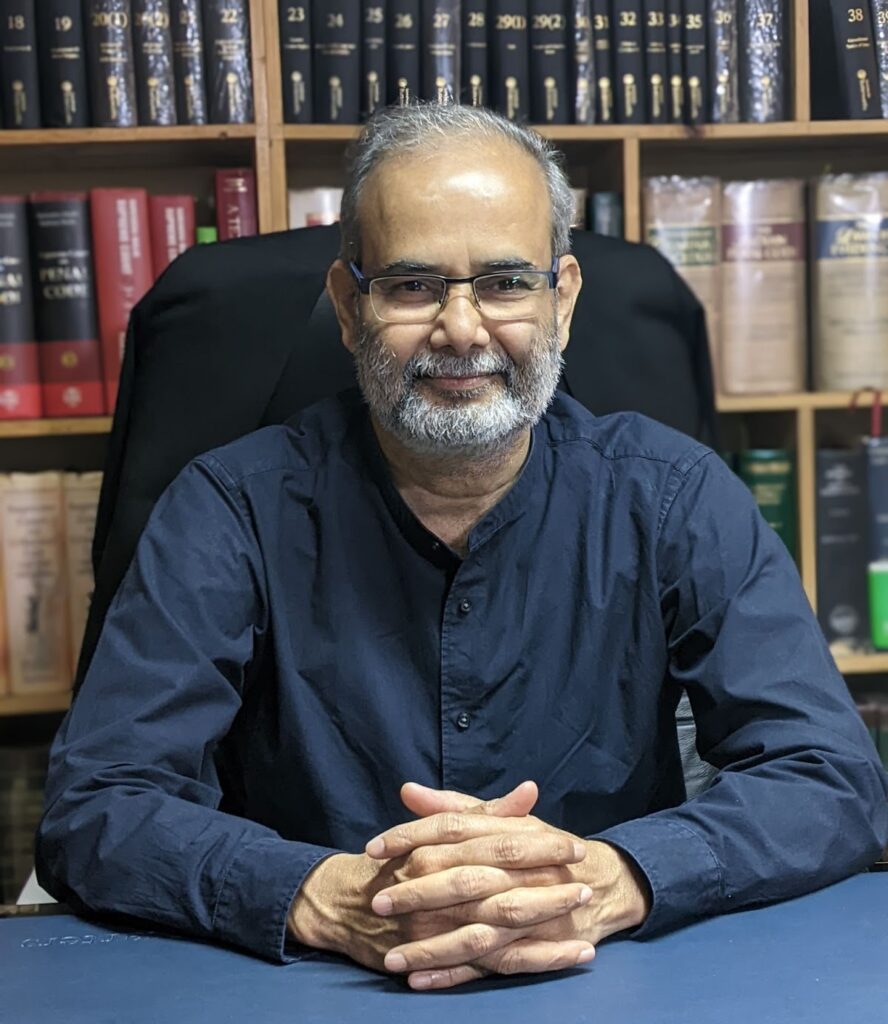

Speaking from his office off Bangalore’s main drag, advocate BT Venkatesh chuckled, thinking about the countless times he represented Lankesh in court. “She would fire in every angle,” Venkatesh recalled. “A gangster would file a case against her. A politician would file a case against her. Some businessmen would file a case against her. She would target anyone who was corrupt.”

Even as legal threats mounted, she continued to publish scathing takedowns of the ruling party, as well as opposition figures and corrupt elites. “What she did was something extraordinary. The grit, the gumption, the kind of way she looked at the magazine. In the span of two years, she transformed it,” Venkatesh said.

Advocate BT Venkatesh at his office in Bangalore. Photo: Phineas Rueckert for Forbidden Stories.

As Lankesh evolved, so too did India. In the mid-2010s, the Hindu nationalists Lankesh had been covering went mainstream. The 2014 election of Narendra Modi catapulted the BJP to power thanks, at least partly, to an expansive network of “IT cells” aimed at spreading positive news about the BJP and attacking its detractors, a group to which Lankesh would come to belong.

According to Joyojeet Pal, an associate professor at the University of Michigan who studies disinformation and politicians’ use of social media, IT cells are structured like a pyramid, with party leaders at the top and a network of influencers at the middle and bottom. The bottom layer plays a key role in creating and trending narratives, while also maintaining enough distance from the top to give leaders plausible deniability if the digital foot soldiers become too extreme. These low-level influencers also work to discredit those who “dissent” against the party line, such as independent journalists or activists.

“There is a certain kind of casting of aspersion on their character or motive based on who they are and what they have covered in the past, and the discrediting happens through that association,” he said. This causes a “chilling effect on journalists who then don’t want to engage online” anymore, he said.

In personal emails to her ex-husband, journalist Chidanand Rajghatta, Lankesh admitted to feeling disillusioned by this pyramidal ecosystem. “When Modi mania becomes a popular mantra, when fascist fury becomes part of daily discourse, when distorted news becomes the mantra of mainstream media, when religious fundamentalism blinds people…I get disgruntled, disenchanted, disturbed,” she wrote in August 2016.

Friends said that by the end of her life, Lankesh seemed unwell: her paper was losing subscribers and accruing debt because Lankesh refused to take on advertisers, and she had become the target of near-constant online harassment by far-right networks connected to the BJP. The trolling would peak after Lankesh would give a speech or post personal photos online that far-right activists used to portray her as a “loose” woman. The character assassination intensified toward the end of her life, with negative content cross-posted in popular right-wing Facebook pages.

In late 2016, about a year before she was killed, her name trended negatively on Twitter after she was convicted of libel and released on bail. Social media posts described Lankesh as a “commie,” “naxalite,” and “prestitute,” a term combining “press” and “prostitute” typically used to attack female journalists. In one widely shared post, Postcard News, which Lankesh named in her editorial, described her as a “known Hindu hater.” The article, which linked to a now-removed YouTube video of a speech Lankesh had given in 2012 and was allegedly shown to at least 5 of her presumed assassins, was shared on social media by Postcard co-founders Mahesh Vikram Hegde and Vivek Shetty.

Angry comments often followed the posts. “Hang them,” one Facebook user wrote.

A Postcard News article was cross-posted on right-wing Facebook pages.

Lankesh did not let on to the magnitude of the trolling she experienced and told friends and colleagues not to take online threats seriously. “[Online trolling] is the last of things you should worry about,” investigative journalist Rana Ayyub remembers Lankesh telling her several days before her assassination. “I didn’t know the extent of how vicious it was,” Lankesh’s sister added.

But in the final months of her life – at the suggestion of a colleague – Lankesh begrudgingly installed a CCTV camera in her house. Friends also pushed her to hire a security detail, but she thought it unnecessary.

Around then, Lankesh and colleagues had discussed launching a fact-checking project, using a decentralized network of WhatsApp groups to counter viral rumors. It wasn’t the first time Lankesh had expressed an interest in fact-checking, but according to her friends and colleagues, the idea of doing it more rigorously and professionally had emerged toward the end of her life. In the days before her death, Lankesh compulsively shared fact-checks on her personal Twitter account, including from Alt News, a fact-checking site run by Mohammed Zubair and Pratik Sinha, who were contenders for a 2022 Nobel Peace Prize for their work on disinformation in India.

Her final editorial, colleagues and family said, was borne from an obsessive quest for truth – but also to admit an error in judgment. Lankesh disclosed that she had accidentally shared a doctored image on Facebook. The photo appeared to show a large rally in favor of the opposition Congress Party but had been photoshopped to inflate the crowd size, fact-checkers later revealed. “There was no intent to incite communal reaction or propaganda,” she wrote. “I only wanted to convey the message that people are coming together against fascist forces.” She concluded with a call to action: “I want to salute all those who expose fake news. I wish there were more of them.”

Journalist Gauri Lankesh. Photo courtesy of Esha Lankesh.

The many-headed hydra

On a typical weekday in April 2022, the sound of typing filled a small office in central Bangalore, muffling the distant honking that pervades the Indian city known for congested traffic. Here, in the newsroom of Naanu Gauri–or “I Am Gauri”–10 or so journalists work beneath a large photo of the assassinated journalist.

After her death, colleagues and friends launched Lankesh’s fact-checking project, establishing the Gauri Media Trust and Naanu Gauri, an independent digital media outlet. Today, the small team produces news analysis and reporting and fact-checks several pieces of fake news per day but struggles to keep up with the torrent of disinformation, according to Muttu Raju, a staff writer.

Journalists at Naanu Gauri work in their office in Bangalore. Photo: Phineas Rueckert for Forbidden Stories.

Journalists and experts said that Bangalore-based Postcard News, run by Mahesh Vikram Hegde, is still one of the biggest players in India’s right-wing media ecosystem. Hegde, a Hindu social media influencer who, like other mid-level, right-wing media players, is legitimized by a Twitter follow from Prime Minister Narendra Modi. In the years following Lankesh’s death, Postcard News incessantly shared misleading information about the murder investigation, seeking to deflect blame onto left-wing groups Lankesh had worked with, and away from the Hindu nationalist outfit connected to the murder.

Picking up where Lankesh left off, Forbidden Stories investigated Postcard News. We found that in the years following Lankesh’s killing, Hegde grew closer to the BJP, co-founding a company that lists an active BJP advisor as a director. Hegde’s media empire, which also includes a popular YouTube channel called TV Vikrama, took off and has over 300,000 subscribers. Hedge’s growth is despite a 2018 lawsuit filed against him for spreading fake news and two police complaints for publishing defamatory content and circulating a possible forged document.

In August 2021, Hegde co-founded a PR firm, Wise Index Media, which lists two additional directors: Shrikanth Kote and Beluru Sudarshana. Sudarshana – a former journalist – is special advisor for e-governance under the current BJP Chief Minister Basavaraj Bommai. He was first elevated to the post by former chief minister BS Yediyurappa in 2019 and again in December 2021 after a cabinet change.

(Bommai did not respond to requests for comment. Through a spokesperson, Yediyurappa refused to comment.)

Mahesh Vikram Hegde, founder of Postcard News.

On its website, Wise Index Media claims to specialize in “Digital Media Management, Political communication, Profiling and Public Relations management, Image Building, Political strategy placement and Data Analysis.”

Kote, the co-founder of Wise Index Media, told Forbidden Stories the company was created to provide visibility to grassroots initiatives and welfare projects in Karnataka but did not comment on the identity of its clients. Sudarshana, he added, was “not an employee of the BJP” but was an advisor working on digitization of government initiatives.

“There’s no political connectivities to e-governance,” he said. “I don’t see any conflict of interest.” (Sudarshana refused to comment.)

While the Wise Index Media site makes no direct mention of Postcard News, hyperlinks under the “about us” section redirect to Postcard pages. On his personal website, Hegde brags about having played a “pivotal role” in Modi’s 2019 reelection campaign. He also appears to have used Wise Index Media as a fundraising vessel for the BJP. In September 2022, he called on temples to make donations to celebrate Modi’s 72nd birthday in a series of social media posts. A handful of these temples drew out checks to Wise Index Media.

(In a WhatsApp message, Hegde responded: “Please send me more jokes.” When Forbidden Stories tried calling, he reiterated that he was “not interested” in responding to our questions.)

Forbidden Stories’s findings align with Hegde’s past statements about his proximity to the BJP, including allegedly telling police that he “had the blessings of several top right-wing leaders” after he was arrested for spreading disinformation in March 2018. The lawyer who initially represented Hegde in court in this case, Tejasvi Surya, is now a prominent member of the BJP and head of the party’s youth wing. (Surya did not respond to multiple requests for comment.)

Postcard News is part of a “very large ecosystem” of media organizations linked to Hindu nationalist groups and the BJP, a digital rights activist who requested anonymity, explained. “It’s a growing media ecology,” they said.

These organizations, experts said, are typically kept at arm’s length, which gives the BJP plausible deniability if they overstep, such as by employing violent or extreme language.

Pal, at Michigan, said in recent years, there has been a “gradual mainstreaming” of media organizations at least loosely affiliated with right-wing entities, including Postcard, The Frustrated Indian and Sudarshan News, a right-wing TV channel. “What they do much more than fake news is suggestion,” he said. “These organizations are often run by very thin staff, and they tap into these mid-level influencers in the pyramid structure [of right-wing groups online].”

“Once they get to a certain point of outreach, they start getting more and more extreme because they need to be even further out than whatever television will say,” he added.

While some organizations operate on a volunteer basis, others have profited off the increasingly lucrative market for on-demand propaganda services, researchers say. “Political parties are now working with a wide range of actors, including private firms, volunteer networks, and social media influencers, to shape public opinion over social media,” a team of researchers from Oxford University wrote in a 2020 report on the growing market for propaganda services.

According to Emma Briant, a fellow at Bard College who studies information warfare, “manipulating the truth has swelled into a billion-dollar business with hundreds, possibly thousands, of service providers worldwide.” “There is a huge range of unregulated industry practices that would widely be considered unethical but not illegal,” she added.

Even before Lankesh’s assassination, these offerings had proliferated in India. One company proposed “weaponized information” services used to “pollute” search engines and “manipulate” current events en masse – proof that the world Lankesh described in her editorial has indeed come to pass. Many experts describe these networks as a hydra – growing back new heads when one is chopped off.

Lankesh was facing up against a similar hydra-like structure, her sister Kavitha said. “It’s not just one organization. It gets seeped out to many, many organizations,” she said. “It can be next door to you.”

The Bangalore City Civil and Sessions Court, where the trial for the presumed assassins of Gauri Lankesh is underway. Photo: Wilhelm Tell DCCXLVI/Wikimedia Commons

A victim of disinformation

In July 2022, the doors of the Bangalore City Civil and Sessions Court opened to a small audience of lawyers and journalists. Seventeen suspects, allegedly linked to the Hindu nationalist cult Sanatan Sanstha and other right-wing groups, were standing trial for Lankesh’s murder.

Journalists and lawyers who spoke with Forbidden Stories described an exceptionally well-run investigation – rare in a country with one of the highest levels of impunity for crimes against the press. A “special investigative unit” created to probe the case got to work quickly: matching bullet casings to similar crimes committed in the past few years, matching empty cartridges to a 7.65mm pistol and identifying the getaway vehicle through CCTV footage. From there, it took six months to arrest an initial suspect: Naveen Kumar. Several months later, investigators filed a roughly 10,000-page chargesheet, naming 17 additional suspects – one of whom is still at large.

The group of assassins, they determined, were part of an “organized crime syndicate” operating across states in southern India. The syndicate is accused of several high-profile bomb attacks in the early 2000s across Goa, the coastal state neighboring Karnataka. Through forensics, investigators tied Lankesh’s death to the murder of three other public intellectuals, also allegedly killed by this group’s members.

Amol Kale, the presumed mastermind of the murder, selected right-wing activists at religious gatherings and trained them to become killers. Parashuram Waghmare, known as “builder” for his compact form, is believed to have pulled the trigger.

According to case files, Kale trained the hired guns over a months-long indoctrination process that included meditation, arms training and religious education. They were made to read Lankesh’s articles and watch videos of her speeches. At least five members of the syndicate were shown the video of Lankesh’s 2012 speech, in which she is heard questioning Hinduism’s roots. Waghmare, the hired gun, could cite lines from the video, suggesting he had been shown the video “repeatedly,” according to a local police investigator who spoke with Forbidden Stories anonymously. (A lawyer representing the accused replied: “As the matter [is] pending adjudication, I am unable to help you.”)

At a meeting in a rented safe house, the plotters decided Lankesh had to be killed “at any cost,” the case file reads. “If left unchecked she would cause disrepute and create a bad opinion about Hindu Dharma in the society,” they allegedly concluded.

Gauri Lankesh's former house in Bangalore. Photo: Phineas Rueckert for Forbidden Stories.

One journalist familiar with the case, who preferred to remain anonymous, said the popular narrative that Lankesh was anti-Hindu, which was reinforced through online and traditional media, played a key role in her assassination. “They decided to target Gauri because of how she was perceived,” the journalist told Forbidden Stories. “The right-wing in Karnataka has been systematically targeting these writers: discrediting, delegitimizing these intellectuals.” The hatred, they added, “grew and grew and grew.”

According to local police sources, the video – downloaded onto Kale’s laptop from YouTube – was one element in a “gradual indoctrination” process. But this video, Forbidden Stories found through a forensic analysis conducted in partnership with researchers at Princeton’s Digital Witness Lab, spread widely across Indian far-right groups, contributing to an intense and vitriolic character assassination that painted her as anti-Hindu well before the plan to assassinate her had been hatched.

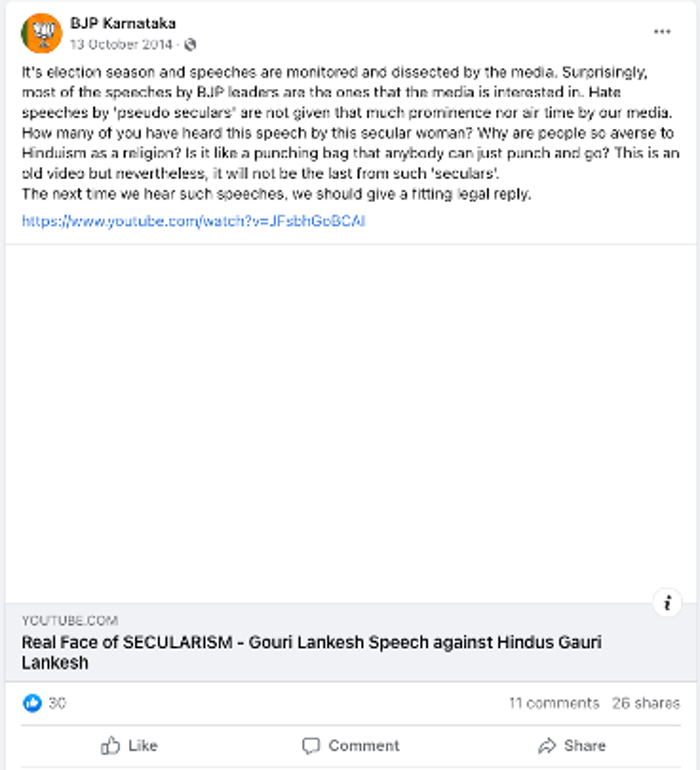

Using open-source tools, researchers found evidence of eight different YouTube links that were shared widely on Facebook, including three that had more than 100 million interactions (likes, shares and comments). In 2014, the official page for the BJP in Karnataka shared the video with a warning: “The next time we hear such speeches we should give a fitting legal reply.”

“The BJP Karnataka post sharing the earliest YouTube video received little engagement from Facebook users but the fact that the video made it there two years after it was originally uploaded speaks to its reach,” Surya Mattu and Micha Gorelick, researchers at Digital Witness Lab, said.

A Facebook post from the official page of the BJP in Karnataka calling on followers to take legal action against anti-Hindu speeches.

(Karnataka BJP did not respond to multiple requests for comment.)

As of April 2019 – the last time it was archived before being taken down – the most popular version of the video had over 250,000 views and hundreds of comments on YouTube. In several cases, the video was published across multiple accounts mimicking the same language, suggesting potentially coordinated posting. In each case, the video is lightly edited and opens with a black screen that flashes the words “WHY I HATE SECULARISM IN INDIA.”

According to Guillaume Chaslot, a former Google engineer who studies how YouTube’s algorithm promotes hate speech, sublimating acts of violence instead of calling for violence directly is a common strategy for gaming YouTube’s algorithm. “As you ban certain types of content based on keywords, people will find other ways to state things,” he said. “Instead of stating, ‘You should kill this person,’ they can say, ‘This is a Hindu hater, he should be lowered to hell,’ things like that.”

In a statement, Google, which acquired YouTube in 2006, wrote: “YouTube’s policies are global, and we apply them consistently across the platform, regardless of the subject or the creator’s background, political viewpoint, position or affiliation. Over the years, we’ve invested in the products and policies needed to help address harmful content, with the vast majority of violative videos removed today with less than 10 views.”

The video was further deformed in the editing process, Forbidden Stories found. According to KL Ashok, who coordinated the event where Lankesh spoke, Lankesh’s speech was not intended as an attack against Hinduism. “It was shortened to include only the part where she says Hindu religion does not have a father or mother. The intention of saying that was to highlight the plurality of the religion. There are thousands of castes and several beliefs,” he said.

On Twitter, the video was less viral, Forbidden Stories and Digital Witness Lab found, but may also have been used for drumming up offline attacks. Our analysis shows that the video was cross-posted from Facebook by an account called @GarudaPurana, belonging to the right-wing activist Bhuvith Shetty, held in connection to several acts of violence and online hate speech. In 2014, Shetty authored a Change.org petition that sought to have Lankesh arrested for “hurting religious sentiments.” (Forbidden Stories reached out to Shetty on Twitter, but he did not respond.)

Lankesh was scheduled to appear in court 10 days after her assassination for a lawsuit against her alleging the speech had disrupted communal harmony. “[I] am facing a case because of this speech,” she wrote on Twitter several months earlier. “I stand by every word I said.”

She never had the chance to stand before the court or defend herself in the eyes of the public, either.

Gauri Lankesh with her niece in Bangalore. Photo courtesy of Sheetal Jain.