When your “friends” spy on you: The firm pitching Orwellian social media surveillance to militaries

Hidden in a trove of leaked Colombian military documents, Forbidden Stories found a confidential brochure – linked to a shadowy company called S2T Unlocking Cyberspace – illustrating how open-source intelligence tools can be used to target journalists and activists.

By Phineas Rueckert

Additional reporting: Omer Benjakob (Haaretz), Jurre Van Bergen (OCCRP) and Felipe Morales (El Espectador)

STORY KILLERS | February 20, 2023

Imagine opening Facebook to a new friend request. You click on the profile and notice mutual friends. The person shares interesting content related to your job or passion on their profile. You don’t know them, but you accept the request.

A few days later, they may send you a message or request to join a closed group you administer. They may also request your WhatsApp number to share a link concerning a cause you’re promoting online. You click the link out of curiosity.

Suddenly, without your knowledge, your device has become a virtual spy machine. Behind the highly-realistic fake account, called an avatar, is an intelligence or police agent who now has access to your personal information and can even activate the device’s camera to spy on you in real time.

Such an online sting operation might typically be used by law enforcement to track criminal gangs, hackers and terrorist outfits. But in a confidential pitch deck accessed by Forbidden Stories, these tools are marketed for potential use against journalists and activists. Forbidden Stories found the brochure in a trove of more than 500,000 documents belonging to the Military Forces of Colombia, leaked to Forbidden Stories by a collective of hackers known as Guacamaya. We traced the brochure to a shadowy cybersecurity company called S2T Unlocking Cyberspace, with current or former offices in Singapore, Sri Lanka, the UK and Israel by matching graphics and tech descriptors on their website with those in the brochure. (S2T did not respond to requests for comment.)

The firm bills itself as an open-source intelligence (OSINT) company, yet the brochure advertises tools beyond typical OSINT, including an automated phishing tool to remotely install malware; massive advertising databases to track targets; and automated influence operations using fake accounts to trick unsuspecting targets.

The “Story Killers” project, a collaborative investigation involving over 100 journalists and 30 media organizations, started from the assassination of Indian journalist Gauri Lankesh, who wrote about the disinformation market. Forbidden Stories investigated how S2T and other OSINT firms have profited from this unregulated market, pitching and selling increasingly sophisticated digital surveillance tools to clients with a track record of spying on journalists and dissidents. These firms are pitching such tools for possible use against civil society and journalists, a heightened concern in the wake of reports of abuse by OSINT firms.

“This brochure, and other publications this year about web intelligence companies, really sheds a light on a new surveillance industry that we didn’t know about that seems to be growing,” Etienne Maynier, a technologist at Amnesty International, said. “We really need to pay attention to this because there is a high risk of it being abused all around the world.”

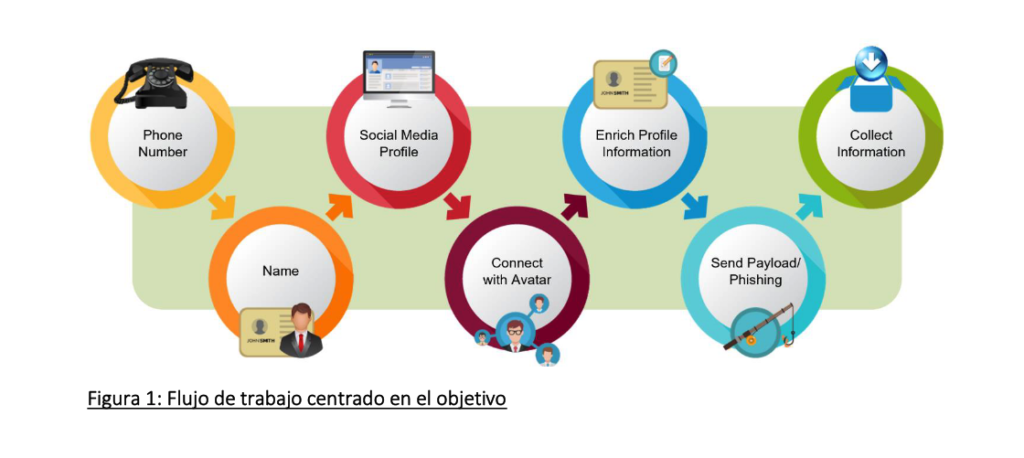

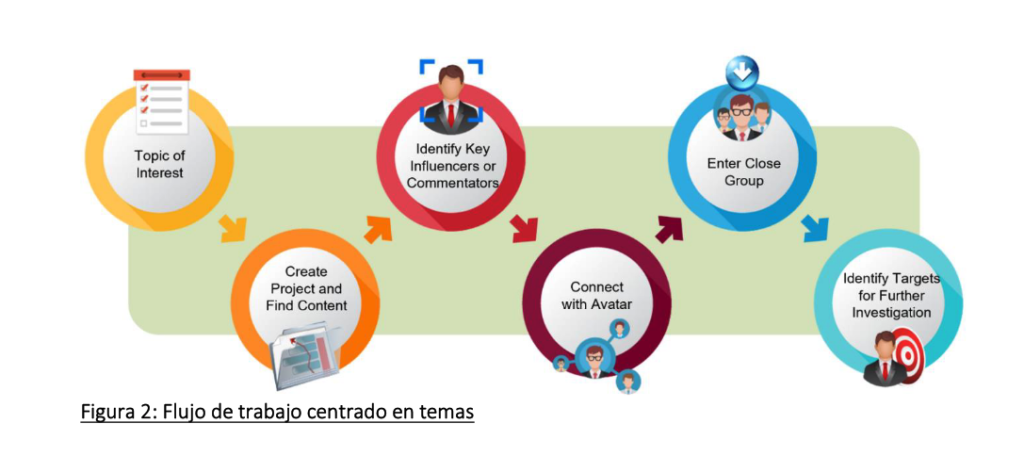

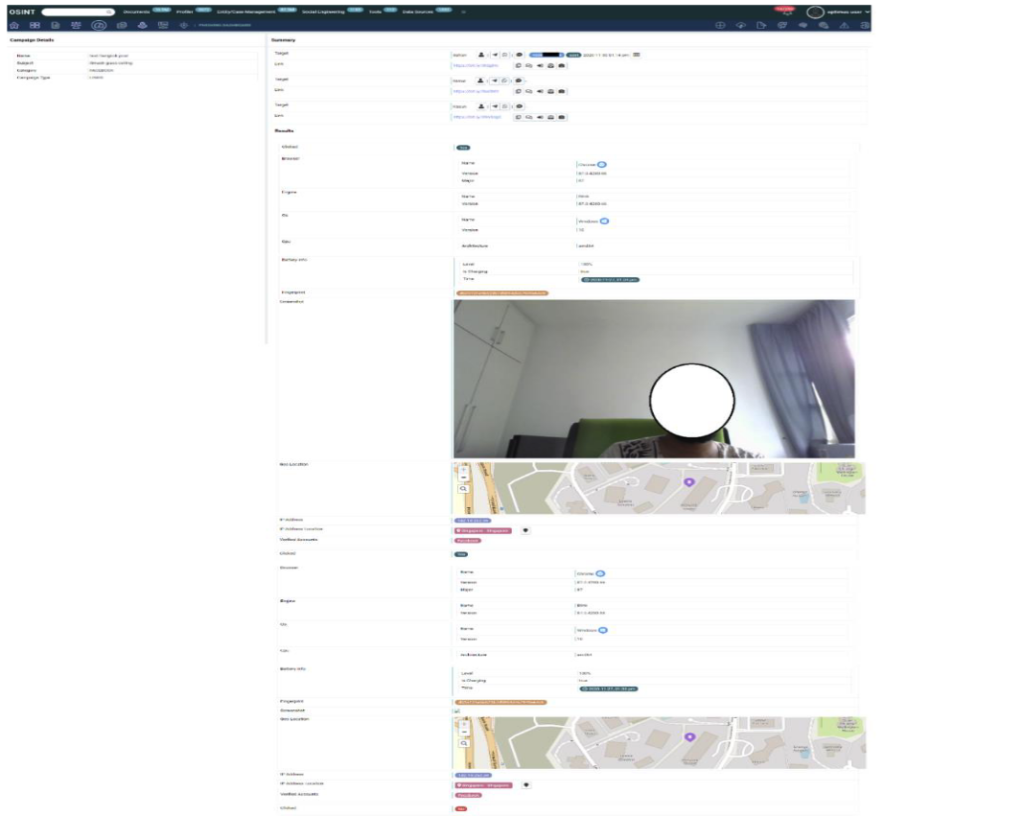

"Workflow" graphics in the leaked brochure show how S2T clients can use avatars to collect information from targets.

Black Mirror

The 93-page S2T brochure reads like a spy novel, or an episode of Black Mirror, with detailed graphics illustrating how the tool operates.

Forbidden Stories shared this document with technical experts, who agreed that the proposed capacities surpass traditional OSINT operations and can potentially be used as a powerful mass surveillance tool. “I haven’t seen such a comprehensive map tying together the whole process and so many techniques so clearly before, especially not explicitly targeting activists,” Jack Poulson, the executive director of Tech Inquiry, a US-based organization that tracks the surveillance industry, said.

“We’ve known for a long time that you have web intelligence platforms, but the narrative was that it’s a platform that’s scraping what is public and making a profile out of it,” but the difference here, Maynier, at Amnesty, said, “is that it’s actually way more intrusive.”

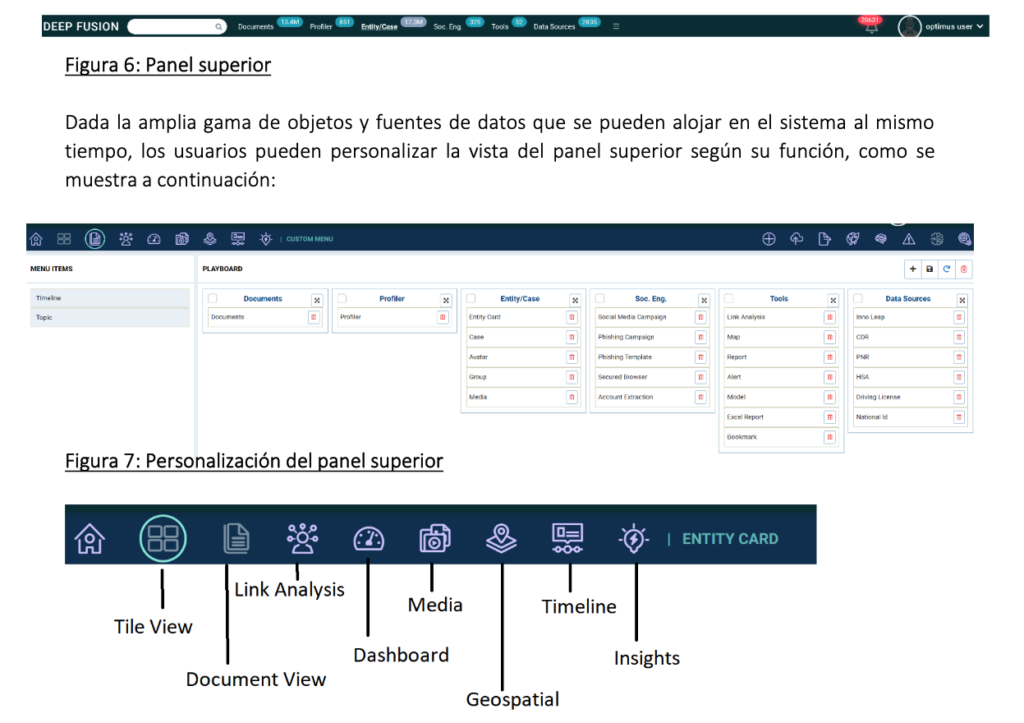

A screenshot of S2T's "Deep Fusion" user panel, part of one of its presumed OSINT tools.

As the brochure describes, the OSINT system integrates facial recognition, artificial intelligence and natural language processing. The tool can, for example, use artificial intelligence to identify a face from a video, such as CCTV camera footage or videos on social media, or map the opinions or sentiments around a term or figure. Also concerning, according to Poulson, is the tool’s ability to influence the public.

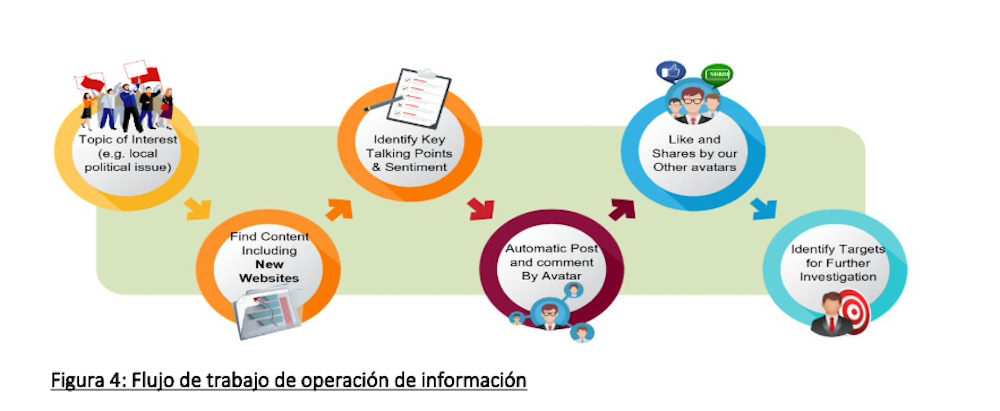

In one chart, for instance, operators start from a “local political issue” and “identify key talking points and sentiment” of a target group. The talking points are then shared on social media using a network of fake accounts—or avatars—programmed to like, share and comment on each other’s posts. These avatars are hidden behind a complex web of proxies making them nearly impossible for social media platforms to detect.

A workflow graphic showing an "information operation."

“The ability to obtain data points and information is only one part of [the OSINT] process,” Dennis Citrinowicz, an Israel-based OSINT researcher, told Forbidden Stories’s partner Haaretz. “The other side of this is of course the ability to conduct an influence campaign. This is not just about passive avatars, but also about social engineering at many different levels, the highest of which is an influence campaign.”

In S2T’s case, influence campaigns are presented as just one method in a broader repertoire of surveillance activities, the brochure shows. The tool makes tracking a target’s location easier: data included in mobile phone apps can be combined with other data sources commonly held by defense and intelligence agencies, such as housing registries or phone geolocation records, to gain a more precise picture of the target’s movements. “We can reach nearly every smartphone user,” it reads.

An example of a successful phishing campaign that triggered the remote activation of a target's camera.

Journalists and activists in the visor

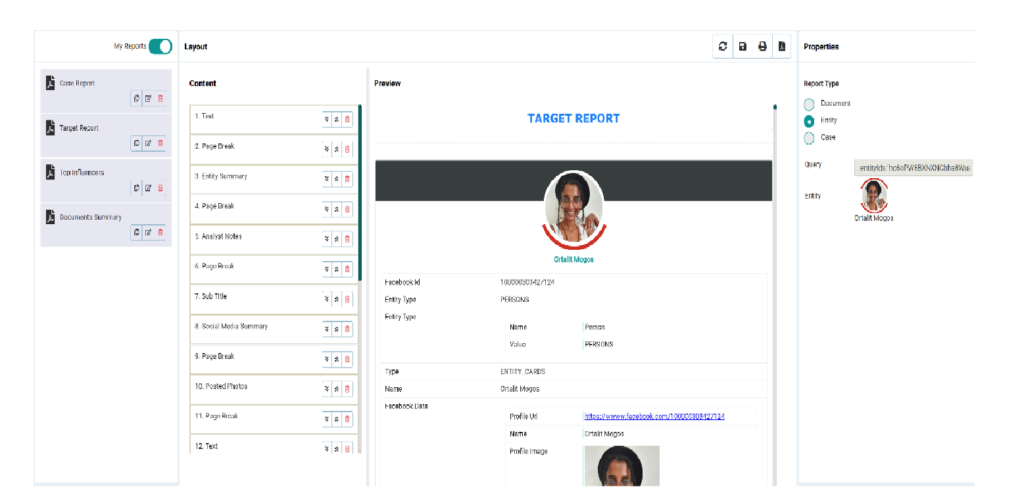

OSINT typically involves gathering public information, like social media profiles, Google search results, and public records, to create detailed profiles of targets, perhaps in the criminal underworld. A former journalist at Ynet, an Israeli digital media outlet, who, according to LinkedIn, now writes screenplays and is a freelance digital content and social media manager, thus does not seem to fit the bill. Yet this profile – Ortal Mogos – appears in a sample “target report” included in the S2T pitch deck. It is unclear whether her account was compromised or her data was automatically scraped for a target report to show clients. (Mogos did not respond to requests for comment.)

"Target report" of former journalist Ortal Mogos.

The brochure was attached to an email sent between Colombian intelligence analysts in March 2022. The Military Forces of Colombia, leaked documents show, met with representatives of seven OSINT firms in early 2022, including an S2T reseller, as part of a tendering process to obtain a new OSINT tool. (A source with knowledge of Colombian internal military affairs confirmed the existence of a project to obtain an OSINT tool but did not know which had been purchased.)

One of these firms, Delta IT Solutions, confirmed to Forbidden Stories that it had sent a proposal for an OSINT system in September 2021 through an intermediary named Anirudha Sharma Bhamidipati, whose name appears in the metadata of the S2T document. In a letter, representatives from Delta IT Solutions confirmed they were “strategic allies” with S2T and had “an open distribution agreement for the Colombian market” but said they were not contracted by the army.

In a cover letter addressed to Colombian military intelligence, S2T promotes its tools as helping to fight “malicious” groups, including: “terrorists, cyber criminals, [and] anti-government activists.” The brochure later shows how operators can “identify targets for further investigation” starting from a “database of known activists.”

That these capacities were pitched to Colombia, where OSINT and surveillance tools have been used to profile and intimidate journalists and activists, also raises concerns. Between 2018 and 2019, dozens of journalists were targets of Colombian military intelligence using an open-source monitoring tool called VoyagerAnalytics, sold by then-Israel-based Voyager Labs. This company met again with Colombian intelligence officials in Spring 2022, documents show. (Voyager Labs did not respond to requests for comment.)

A workflow graphic showing how a database of activists can be used to identify targets for further investigation.

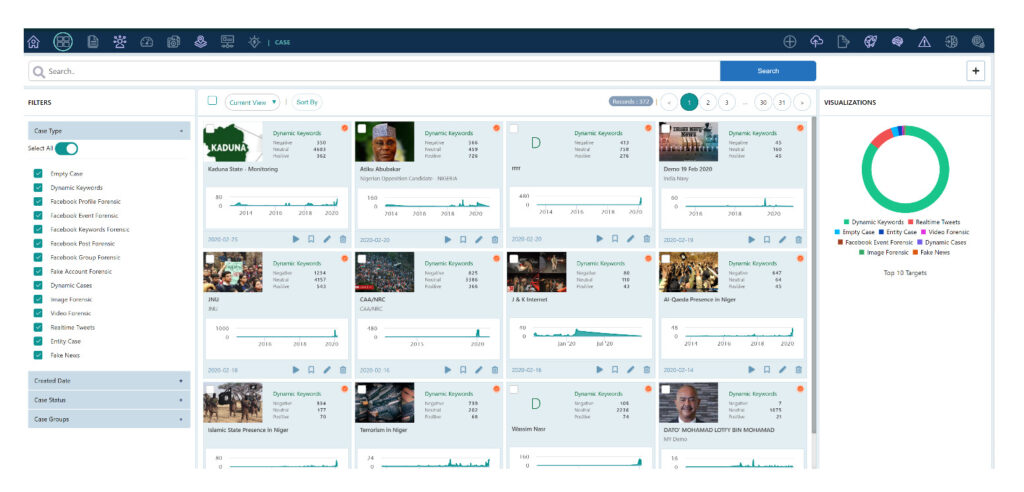

One screenshot suggests an Indian client may have been interested in acquiring this tool for monitoring protest movements on social media. Among at least a dozen case studies from February 2020 are examples showing how the tool was used to analyze “dynamic keywords” related to student protests in 2020 against India’s 2019 Citizenship Amendment Act and what is likely a reference to 2019’s Jammu and Kashmir internet shutdowns.

Even tools aimed only at data collection could be used against journalists to silence critical voices, experts warned. “This is the reconnaissance phase of a level of surveillance that ends with either compromising accounts or compromising devices,” Eva Galperin, director of cybersecurity at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, said speaking of OSINT in general. “It is directly linked to arrests, to visits from the security apparatus, to beatings, to torture, to intimidation, to lawsuits.”

An example avatar that may have been used to collect information from social media platforms.

A global market

S2T was founded in 2002 by entrepreneur Ori Sasson. It claims to have dozens of clients across five continents and employs people from intelligence agencies in the UK, the US, Russia and Israel, as well as local law enforcement in the Middle East, South and Central America and Asia. Forbidden Stories identified clients in Singapore and Israel and possible customers in Bangladesh, Turkey, Sri Lanka, India and Malaysia. According to S2T’s website, other clients include “a Media group in Central America” and a “South American nation” where its tools were used to find “relevant information about the mastermind behind a kidnapping.” The brochure also discusses demos perhaps given in 2020, including to the Indian Navy and Dato’ Mohamed Lofty Bin Mohamed Noh, a businessman in Malaysia.

Screenshot showing case studies from February 2020 monitoring "dynamic keywords."

Forbidden Stories identified an Israel-based company as a possible reseller of this technology. The company, KS Process and Software Ltd., shares at least one address and phone number with S2T. On its website, this company boasts of social-engineering tactics used to trick targets into sharing personal information. According to a two-page brochure downloadable from its website, the company appears to have worked on behalf of a “Turkish political party,” using social media avatars to join closed groups and collect intel on opponents.

A former S2T employee who spoke anonymously confirmed the firm has long pitched active intelligence-gathering tactics to obtain information on a target, pitching to state and private clients. One recent report on a similar cybersurveillance firm found such tools were used to profile potential hires and monitor NGOs on behalf of private clients.

“You think because it’s open [source], it’s ok, but if you connect open sources from leaks to form a profile of someone or you use data that someone is not conscious that their digital activities creates, then it’s not really ok,” they added.

A screenshot from S2T's website.

While it is unclear whether these entities purchased S2T’s platform, Forbidden Stories and its partners identified one probable client: Bangladesh’s Directorate General of Forces Intelligence (DGFI).

Bangladesh Home Minister Asaduzzaman Khan. (Photo: Prime Minister's Office/Wikimedia Commons)

An S2T subsidiary appears to have made a shipment to the DGFI in December 2021 or January 2022, which Forbidden Stories confirmed through concordant trade data. The revelation follows a Haaretz investigation that found Bangladesh’s intelligence services purchased other Israeli-linked tech in 2022, including spying vehicles that could intercept mobile and internet traffic.

Bangladesh’s solicitation of such tools aligns with its public statements. In January, according to The Business Standard, the country’s Home Minister announced that it would be introducing an integrated lawful interception system “in a bid to monitor social media platforms and thwart various anti-state and anti-government activities.”

The chilling effect

In Colombia, journalists previously profiled by OSINT tools still don’t know why they were targeted three years ago. “That the press would be subjected to that type of investigation by the state’s military forces, and nothing happens, it makes you ask all sorts of questions,” journalist María Alejandra Villamizar, who was included in a target report after interviewing a rebel leader in Havana, said in an interview with Forbidden Stories.

Journalists who covered the scandal, known in Colombia as the “secret folders,” were threatened. Ricardo Calderon found a note stuck to his car with an image of a casket when he began reporting on military surveillance. Family and sources were also threatened. “The process was simultaneous: intimidate the journalists and intimidate the sources,” Calderon said. “The point was to torpedo the investigation by attacking from both sides.”

Those reporting critically on the Military Forces of Colombia, including multiple reporters at Rutas del Conflicto, an independent media outlet that covers human rights abuses, corruption and land speculation,were also profiled using OSINT tools. “The interpretation was, ‘This is a leftist media outlet, an opposition outlet’ and in this country, historically, those who have been stigmatized as distinct, as different, have been killed, threatened, forced into exile,” a reporter from Rutas del Conflicto, who preferred to remain anonymous due to security concerns, said.

Colombian military members in 2013. (Photo: Pipeafcr/Wikimedia Commons)

In 2021, Meta, the parent company of Facebook and Instagram, began to crack down on OSINT firms and companies involved in the private surveillance industry. In a report on the “surveillance-for-hire” industry, Meta’s threat intelligence team identified three stages of surveillance – reconnaissance (silently collecting information), engagement (contacting targets) and exploitation (hacking and phishing). The investigation concluded, “targeting is in fact indiscriminate and includes journalists, dissidents, critics of authoritarian regimes, families of opposition and human rights activists.”

In January, Meta sued Voyager Labs for using 38,000 fake accounts on Facebook to scrape information for their clients, amounting to 600,000 users for at least three months. “This industry covertly collects information that people share with their community, family and friends, without oversight or accountability, and in a way that may implicate people’s civil rights,” a Meta representative said in a statement.

In the wake of such revelations, security experts told Forbidden Stories they worried these tools pose a risk of misuse.

“If you are a government that’s interested in intimidating and threatening journalists, you’re likely to find out a lot of information about their patterns of daily life, who their family members are, the kind of biographical information that would give an unfriendly government quite a lot to work with to intimidate a journalist from a story,” Rachel Levinson-Waldman, managing director of the Brennan Center for Justice’s Liberty & National Security Program, whose work focuses on how this technology affects activists, said.

The Colombian journalists illustrate the chilling effect of these OSINT tools. Some have been forced to adapt their reporting practices to respond to new digital threats. In the weeks after they learned that they had been profiled, journalists at Rutas del Conflicto began group therapy sessions, according to a Rutas journalist. Many stopped including their bylines and posting on social media. Some left the profession.

“You start to evaluate your life choices,” the Rutas journalist said. “You wonder if your job is going to turn into a constant source of persecution.”