- Temps de lecture : 15 min.

In the Brazilian Amazon, land for sale on Facebook

In the third installment of “The Bruno and Dom Project,” which continues the work of British journalist Dom Phillips on the pillaging of the Amazon, Forbidden Stories unveils an organized land-grabbing system headed by a powerful landowner. The same landowner is allegedly implicated in a string of large forest fires that decimated the Amazon in 2019. The investigation also reveals that despite Facebook’s promises, the social media platform is still used to facilitate land sales in the Amazon, including sales of protected public lands.

Disponible en

By Karine Pfenniger

Translated by Amy Thorpe and Sophie Stuber.

With Mariana Abreu and Daniel Camargos (Repórter Brasil).

This article relied on research and data analysis conducted by Ruan Martins.

Eduardo Goulart (OCCRP) contributed research.

In a WhatsApp audio message, “João” lightheartedly listed the assets of his lands for sale in the heart of the Amazon rainforest.

“These are immense areas, large farms,” said “João,” who shared only his first name.

Forbidden Stories had contacted him posing as a potential client interested in a land listing posted on Facebook. In our exchanges on WhatsApp, “João” described the parcels of land for sale. They are “not deforested,” but “João” offered to “fell the trees at his own risk” for interested clients.

The available land parcels are up to 8,000 hectares, larger than 11,000 football fields, sold for 1,200 reais per hectare (about 220 euros), “João” said. In principle, selling these lands, which are claimed by the Pará state, is illegal, but the listing was publicly available on the world’s largest social network. Dozens of people, including “João,” sell Amazonian land on Facebook.

Dom Phillips uncovered this phenomenon as early as 2019 while investigating deforestation and forest fires in the Pará state—part of his relentless coverage of the pillaging of the Amazon. The British journalist found a listing on Facebook from a woman named Nair Rodrigues Petry, known as “Nair Brizola,” for protected land.

The third installment of the “Bruno and Dom Project” continues Phillips’ investigation into this landowner, revealing an organized land-grabbing system that visibly benefitted Brizola. Behind it is a man allegedly implicated in a series of fires that devastated the Amazon in 2019.

Forbidden Stories also discovered that despite prior journalistic investigations and the platform’s counteractive measures in 2021, people are still listing land at the heart of the Amazon, including public and protected areas, on Facebook.

Facebook, fire, and forests

In August 2019, the Amazon burned. In just one weekend, from August 10 to 11, Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research (INPE) recorded 1,457 hot spots in the country, an increase of close to 2,000 percent compared to the same period the year before. Dubbed the “Dia do Fogo” (“Day of Fire”) in Brazilian and international media coverage, the destruction of the Amazon sparked outrage from political leaders, including French President Emmanuel Macron. In response, then-president Jair Bolsonaro denied the existence of the fires during his opening speech at the 74th session of the UN General Assembly.

In Brazil, federal prosecutors suspected foul play by local landlords and opened an investigation, which is still ongoing.

As fires raged across the district of Cachoeira da Serra in southwestern Pará, a landowner misled journalists reporting on the story and claimed that the perpetrators of the fires were officials from Chico Mendes Institute, the federal agency in charge of biodiversity conservation in Brazil. Ricardo Salles, then-Minister of Environment, retweeted the claim and Bolsonaro ordered a police investigation.

Facebook post by Nair Brizola for the sale of a plot of land located in a biological reserve, July 2019. (Photo: Meta)

But Brazilian outlets soon found that the landowner in question, Nair Brizola, had recently been fined more than one million reais (around 240,000 euros at the time) by the Chico Mendes Institute for having destroyed “by fire” close to 71 hectares in a biological reserve near Cachoeira da Serra. Furthermore, Brizola declared that she owned a gigantic piece of land on this reserve, where private ownership is illegal.

A few months later, Phillips set off on a reporting trip in the Amazon with Repórter Brasil photographer João Laet and journalist Daniel Camargos, now a member of the consortium coordinated by Forbidden Stories. While exploring the partially burnt and deforested terrain, the two reporters discovered that Brizola had put land on the biological reserve up for sale on Facebook.

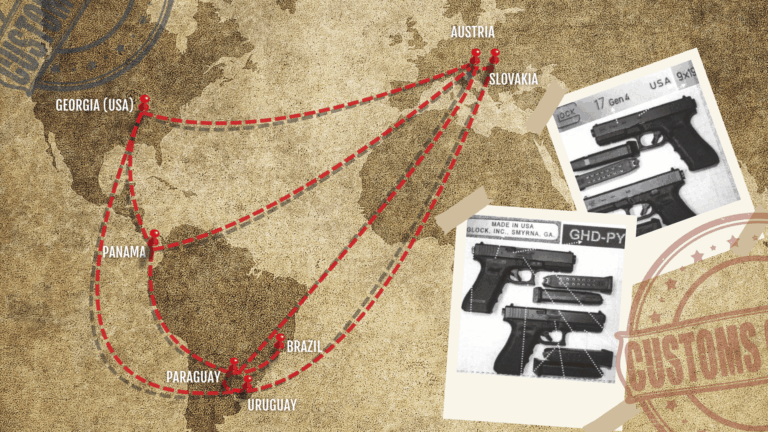

Through the listing discovered by Camargos and Phillips and an analysis of administrative documents for the land claimed by Brizola, Forbidden Stories traced Brizola’s shady dealings back to one of the main suspects behind the “Day of Fire,” Agamenon da Silva Menezes, a landowner and president of the rural producers’ union of the city of Novo Progresso, in the Pará state. This powerful man appeared to have developed an elaborate land-grabbing system with the help of his son-in-law, Wilmar Santos Melo, who registered dozens of parcels of land situated in public and protected areas in Pará—totaling close to 75,000 hectares, more than seven times the surface area of Paris. Brizola’s tract of land was part of da Silva Menezes’ system.

An environmental framework used to protect Brazil’s forests from deforestation, among other things, is at the heart of da Silva Menezes and his son-in-law’s scheme. Established in 2012, the Rural Environmental Registry (CAR) requires landowners to provide environmental information about their properties, including details on the vegetation and soil.

The system is self-reported and the validity of entries is rarely inspected. Simply registering a desired parcel in the CAR generates an official document from the registry. This is not a property title, but land-grabbers take advantage of the system by misusing the official documents to claim ownership and to acquire new documents that legitimize the property—even if they are not the rightful owners or if the parcel is on public land.

This large-scale exploitation would not be possible without the complicity of private sector professionals who know local legislation inside and out.

“Usually, in every municipality, you have maybe two to three people who know everything: who owns what, who is where, what the prices are. They are the guys who do the CAR [registrations]. They also do the procedure at the land agency. They kind of control this market,” Brenda Brito, researcher at the Amazonian NGO Imazon, explained.

Journaliste menacé

Phillips previously interviewed Brito while researching the legal loopholes that facilitate land-grabbing for his book.

Santos Melo, da Silva Menezes’ son-in-law, registered at least 600 land parcels through the CAR in Pará. Some 77 of them, including the one under Brizola’s name, corresponded to areas either entirely or partially in conservation units, protected public zones where private ownership is prohibited.

“It’s a shame because it’s impossible to have any kind of property inside these places,” Rômulo Batista, a spokesperson from Greenpeace Brazil, told Forbidden Stories when we shared this figure with him. (Editor’s note: in practice, there are numerous conservation units in Brazil where the expropriation of former owners has not yet concluded.)

Nair Brizola was fined by the Chico Mendes Institute in 2019. (Image: Repórter Brasil / Forbidden Stories)

Contacted by Repórter Brasil, da Silva Menezes confirmed the CAR registrations and his connection to Santos Melo, who was acting as an official for the rural producers’ union that da Silva Menezes presides over in Novo Progresso, Pará. According to da Silva Menezes, the union registered “more than 600 properties [located] in conservation units” and supplied “many [land] services.”

Santos Melo declined to comment when contacted through Agamenon Menezes.

Separately, Brizola assured Repórter Brasil that she had the documents to prove that she had owned the land in question since 1994—before the establishment of the biological reserve. She gave Phillips a similar response in 2019.

“I paid for this property. I have the right to be here,” she told Repórter Brasil.

Brizola also claimed she had no memory of the plot being registered in the CAR, which Santos Melo did in 2015.

Soutenez Forbidden Stories

“He provoked and provoked and provoked [me], until he got what we deserved”

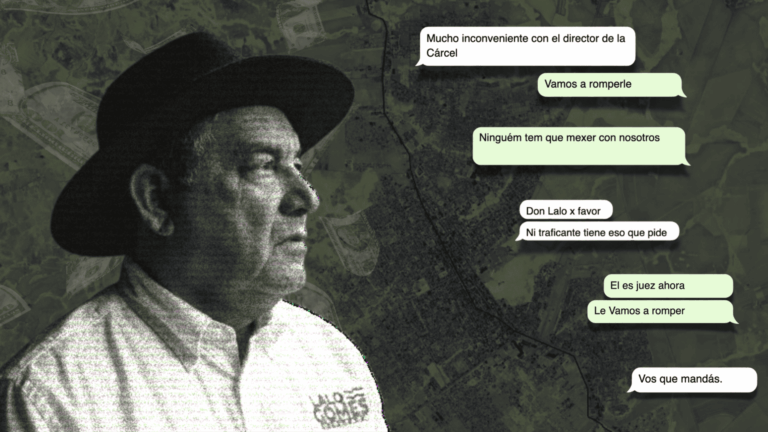

Da Silva Menezes is close to political power at the municipal and federal levels. He has been described by the press as a land-grabber who will stop at nothing to achieve his goals.

In a 2017 interview with online media outlet Mongabay, he spoke about obtaining a piece of federal land where several landless peasant families had set up a camp.

“If they leave peacefully, good. If they don’t, we’ll force them out. Whichever way they hit us, we will react in the same manner. If they use clubs, we’ll use clubs. If they use knives, we’ll use knives,” he said. “In the end, we’ll make them leave.”

The following day, six armed men attacked the camp, firing rounds into the air, according to Mongabay. Although nobody was hurt during the incident, the farmers were forced out, and their leader, Aluisio Sampaio, was shot dead in broad daylight one and a half years later.

Sampaio, also known as “Alenquer,” had been a regular critic of da Silva Menezes, who he said sent him death threats. While the main suspect behind his killing was arrested, the man was later shot dead upon his release from prison.

Questioned by Repórter Brasil, da Silva Menezes first claimed to never have spoken to “Alenquer,” but later added: “He provoked and provoked and provoked [me], until he got what he deserved. The people who killed that guy are the ones who were set up [in the camp].”

Despite being prosecuted several times, da Silva Menezes was never imprisoned. The police questioned him as part of the ongoing investigation into the “Day of Fire” and searched his home and offices. Da Silva Menezes denied any guilt and even refuted the existence of the “Day of Fire,” which he claimed was fabricated by the media.

His son-in-law appeared in a federal police report, consulted by Forbidden Stories, from the investigation that showed that he later registered four parcels of land that had been deforested during the “Day of Fire” in the CAR. He is still registering new parcels in the CAR of Pará, according to the registry’s public platform, even as most of his registrations are being looked into by the authorities—a sign Santos Melo may have aroused the suspicions of the administration in charge of the CAR.

The Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office declined to comment on Santos Melo’s registration activities, citing the confidentiality of the “Day of Fire” investigation.

In 2016, Brazil’s Federal Environmental Protection Agency (IBAMA) fined Santos Melo 111,500 reais (around 30,000 euros at the time) for providing “false information in administrative procedures for rural environmental registration” for several plots in Pará. IBAMA told Forbidden Stories that the fine is currently being contested in court.

As for Brizola, Forbidden Stories learned that a court in Pará dismissed both her civil and criminal cases. The federal prosecutor’s office has appealed the decisions, but she still put land up for sale on Facebook again in 2020.

The biological reserve land claimed by Nair Brizola, 2019. (Photo: João Laet / Repórter Brasil / The Guardian)

Public land in the Amazon for sale on Facebook

Listings like Brizola’s are flourishing on Facebook. Forbidden Stories identified more than 60 suspicious listings for land in the states of Amazonas, Pará, and Mato Grosso. Over the course of three weeks, for these three states, seven posts like this were published on the social network every day on average, according to our estimations.

In the sample of posts we consulted, the land parcels were often immense, partially deforested, and without proper land titles. The prices were usually very low—450 reais per hectare (about 82 euros) at the lowest. The bargains could indicate land-grabbing.

“Normally, the sale [of grabbed land] happens at a price well below market value,” explained Heron Martins from the Center for Climate Crime Analysis (CCCA), an NGO that denounces corporate contributions to global warming.

In return, the buyer risks never regularizing the ownership of the property.

When Forbidden Stories contacted “João,” posing as a client, he claimed to be selling large swaths of rainforests for 1,200 reais per hectare (around 220 euros) in Almeirim, in northern Pará—three times less than the municipality’s average market price. “João” also proposed other services in his WhatsApp audio messages.

“The environmental legislation [in Brazil] is strict, but we have ways to get around it and deforest,” he said. “I have ways of cutting and burning down the trees in mid-October. Once the rain stops, it burns by itself…When December arrives, the rain starts up again in the region. We can drop seeds from planes, and the farm is pretty much ready.”

With such techniques, a virgin forest could be transformed into pastureland in just a few months. This “environmental operation” would cost between 700 and 800 reais (between 128 and 146 euros) per hectare, including labor, “João” said.

“João” did not hesitate to offer to deforest “20 to 50 percent” of the land he was selling, even though federal law bars deforestation of more than 20 percent of a land parcel’s surface area in the Amazon rainforest.

“If they are offering to deforest 50 percent of the area, it means that what they are offering is illegal,” Batista told Forbidden Stories.

Document that “João” provided for an application for a land title from the Pará Land Institute (ITERPA). (Photo: Forbidden Stories)

“João” also told us that the land title was still being acquired and sent us documents showing the request. He claimed the process could be accelerated for 400 reais per hectare. At that price, “João” claimed he could obtain the document certifying ownership within six months. Otherwise, it may take anywhere from five to 20 years, he said.

The Pará institute in charge of land title regularization, ITERPA, did not respond to Forbidden Stories’ request for comment.

The areas of land “João” was selling were vast. Most exceed the limit of 2,500 hectares that, in principle, require the National Congress’s validation to be privatized. But the CAR registration certificates that “João” sent us revealed that he worked around this by splitting the tract of land into four smaller, side-by-side parcels. Each was about 1,400 hectares—under the size limit.

Suivez-nous et partagez

nos histoires

State of Pará, as seen by Phillips and Repórter Brasil in 2019. (Photo: João Laet / Repórter Brasil / The Guardian)

What’s next?

In total, Forbidden Stories spoke with eight people actively selling land on Facebook, each time posing as a potential client. Several of them told us they did not possess the title to the property, which is required for selling land. One of the sellers offered us around 1,360 hectares in a federal extractive reserve in Pará, a protected area where private land ownership is, in principle, illegal. After an investigation by the BBC revealed that Facebook was being used to sell grabbed land in the state of Rondônia, the company pledged to ban the sale of land in ecological conservation areas on its commercial spaces like Marketplace in 2021.

When contacted by Forbidden Stories, a spokesperson for Meta said that the company is reviewing listings on Facebook Marketplace to find posts that violate their policies and said that the company did not allow “the buying or selling of land in ecological conservation areas across our commerce surfaces.”

“The determination of whether a particular piece of land is permitted to be sold involves a complex legal analysis that is the responsibility of local courts. Besides reviewing reports of potentially violating content, Meta also complies with valid local court orders,” the spokesperson told Forbidden Stories.

Lucas Ferrante, an environmental researcher at the Federal University of Amazonas, told Forbidden Stories that the unlawful sale of land on Facebook occurs frequently.

“This is a common practice [among] criminal organizations,” he said. “And it shows that the inspection bodies are not working in the area.”

Often linked to other crimes, such as the violent displacement of indigenous communities and small-scale producers, land-grabbing in the Amazon has consequences beyond its borders. To combat climate change, Brazil promised to reach zero deforestation by 2030.

“Without fighting against land-grabbing, it will be impossible to achieve this [goal],” Batista from Greenpeace said. “We need a serious fight against these problems in the Amazon that are killing not only the forest but some of the people that live in these places.”

Phillips was on a quest for solutions. His article on the fires in Pará in 2020 uncovered Brizola’s Facebook land listing, but even he did not have the answers to these complex problems.

“We know why Amazon forests like this burn, but given Brazil’s current political situation, there are no solutions in view,” he wrote.

Phillips and Camargos reporting in the Amazon. (Photo: João Laet / Repórter Brasil / The Guardian)

À lire aussi